Bhaskar Parichha

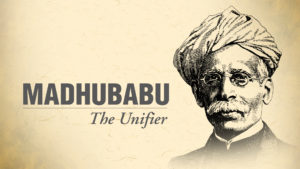

THE PEOPLE OF ODISHA IN THE EARLY PART OF NINETEENTH CENTURY FACED AN UNPRECEDENTED IDENTITY CRISIS AND ONLY A MADHUSUDAN COULD HAVE RISEN TO THE OCCASION.

Madhusudan Das, or ‘Utkal Gaurav’ as he is fondly called, had many firsts to his credit: he was the first graduate, first post-graduate and first law graduate of Odisha .But more than these seminal achievements, the renaissance era in Odisha was led by Madhusudan. Even though born in a family of an erstwhile landed aristocracy, he made a new beginning and resurgence Odisha needed a leader like him. Indeed, none other than Madhusudan could have given the state a new birth, a new identity.

Madhusudan is singularly remembered for his relentless effort to bring together the disparate Odias and the unification he struggled to attain was stupendous. Madhusudan’s unification theory didn’t hinge on linguistic prejudice. The element of linguistic nationalism found in his scheme of things was need of the hour. The people of Odisha in the early part of the nineteenth century faced an unprecedented identity crisis and only a Madhusudan could have risen to the occasion.

Madhusudan strongly believed ‘Odisha was a colony of a colony’. As compared to other provinces, problems in Odisha were grave: there was a serious threat to the culture and language in the backdrop of the half-baked hypothesis that ‘Odia Ekta Swatantra Bhasa Nae’ (Odia is not a language).

Madhusudan’s profound knowledge about Italian and German Unification must have impelled him to propound the theory that language is a significant factor to connect the people and it is the only language that provided a basis for emotional integration. If Madhusudan was born in distinctly historical circumstances, he had to strive in mobilizing the people. Besides the danger to the Odia language, education-ally and economically Odisha was lagging behind by at least half a century. Bengali apathy and British imperialism contributed shoddily to the decline.

Fascinatingly, Madhusudan didn’t put a fight with the neigh-boring Bengal aristocracy for their dominance. He just wanted the onslaught on the language to stop and demanded the respectability that Odias deserved. This demand was again within the framework of a single administration.

As President of the ‘Utkal Sabha’, Madhusudan was resolute to elevate the Odia language and literature and to unite the Odia-speaking tracts. Supporting the view of Madhusudan, no less than Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy, argued in the British House of Lords that the natural entity of Odisha had been erroneously disintegrated and the people were being forced to accept other languages.

“Utkal Sammilani’ was the binding force. In 1903, Madhusudan convened the historic Utkal Sammelan at Rambha, Ganjam. The native princes, lawyers, intellectuals and journalists who attended this convention displayed a hitherto- unseen sense of patriotism. Rambha conference was the precursor to the unanimity.

If Madhusudan’s claim was supported by Lord Curzon, it found sympathetic mention in the Montague- Chelmsford Reforms (1919) and the Simon commission Report (1927). Eventually, Odisha became a separate state under the government of India Act, 1935. With effect from 1st April 1936, a separate Governor’s Province of Odisha was established. Odisha became the first linguistic province in the Indian union. The rest, as they say, is history.

(Source: www.madhusudandas.org)