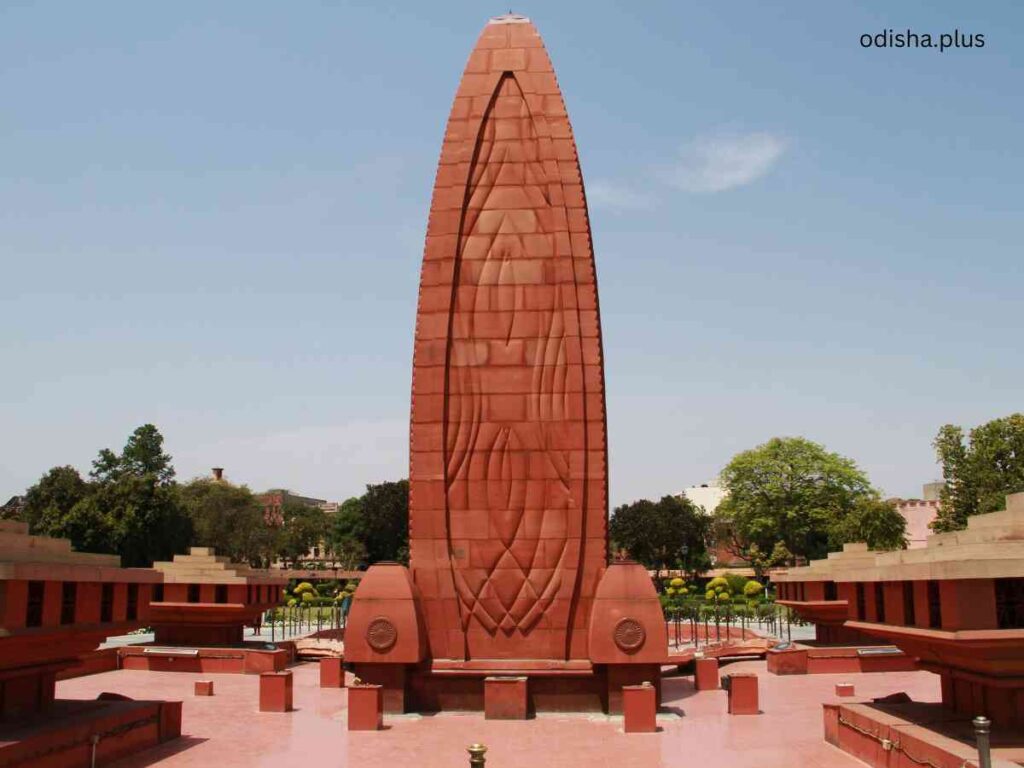

Jallianwala Bagh massacre stands as a harrowing reminder of colonial oppression, where British troops under General Dyer opened fire on thousands of unarmed civilians, marking a pivotal moment in India’s struggle for independence

Prof Satya Narayan Misra

One hundred six years ago on 13th April 1919, Brigadier General Dyer had ordered firing at a crowd estimated at between 5000 – 30,000 which was completely peaceful, and non-violent. He had not given any advanced warning when the fire was opened. His bodyguard Sergeant Anderson later noted that the crowd ‘seemed to sink with the ground, with a flutter of white garments.’ The firing squad of 50 fired exactly 1650 rounds non-stop for about 10 minutes until the entire crowd had fled or fallen.

An estimated 400 Indians, including children, old, and women died and around 1000 were injured and were denied healthcare at a nearby hospital. The wall still bears testimony of the bullet holes. Gurkhas, who were used predominantly fire later remarked with evident relish ‘While it lasted it was splendid’. Was it a reflection of racism that one associates with imperialism or the handiwork of an isolated cold-blooded bigot, Brigadier Dyer?

This dastardly act, which still brings a feeling of revulsion to every tourist that visits this monument, was enquired into by the Hunter judicial inquiry committee in October 1919. It had five British members and three Indians, including the eminent jurist Setalvad and Kantilal Sah, a London-trained lawyer, who played both a diabolical part, being part of drafting the Rowlatt Act and yet playing a valiant role during the deposition before the Hunter Committee.

Richard Attenborough’s famous biopic of Mahatma Gandhi has a highly emotive and largely fictional scene of the massacre. Recently a series by Ram Wadhwani ‘The Waking of a Nation’ is also streaming, reminding us how history is written & how it is manipulated. However, Kim A. Wagner’s book ‘The Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre’ (2019) is far more poignant and fills up a critical void in understanding the conflicting perspective of this great human tragedy during British rule.

Perceval Spear, the historian, observes that “Jallianwala Bagh was a scar drawn across Indo-British relationship, deeper than any which had been inflicted since the mutiny of 1857. It became a remarkable signpost towards Indian Independence.” Punjab in 1919 was a place of widespread agrarian unrest caused by monsoon failures, food scarcity, and high prices, to which WW1 added pressure.

A large number of soldiers who fought in WWI on the side of the British died or were handicapped. The Rowlatt Act (1919) was a major petard of this, as it was carefully calibrated to punish the extremists while rewarding the moderates and a travesty of what goes for the British sense of fairness and justice!

On April 10th, a peaceful Gandhian Hartal turned violent with an angry mob rampaging through the city. The town hall was set on fire and its telegraph office was looted. The National Bank and the Alliance Bank were also looted and the Managers were set on fire. Twenty Indians died in police firing. In retaliation, five British Civilians were lynched to death. The most emotive attack was on Ms. Marcella Sherwood, the 45-year-old Superintendent of the City Missions who was cycling into the city alone to close down the five schools she managed.

She wanted hundreds of students in her charge to go home safely. She was mercilessly beaten by a group of men who left her where they thought she was dead. She was taken to the Fort where she hovered between life and death. One of Ms. Sherwood’s first visitors was Brigadier General Dyer who had moved to Amritsar to help to restore order in the city. The tele serial ‘The Waking of a Nation’ captures these moments of history poignantly.

As peace was returning to the city, belying reason, on April 13th Dyer marched his troops with their armoured cars through the city prohibiting gatherings of more than eight people. The ban was not widely published. The Manual of Military Law required the issue of a formal warning before opening fire on civilian rioters and the use of minimum force, if possible, only firing in the air. But Dyer conducted the shooting as a military operation against enemy troops, reasoning that he was the one under attack. During his prolonged examination by the Hunter Committee, he said he would have probably used the machine guns if he could have squeezed his armoured cars into the bagh!

Brigadier-General Dyer’s action came for discussion before the House of Commons on 8th July 1920 where the resolution of censure was upheld by 230 – 179 votes. It was Churchill’s speech that tilted the scale against him when he said “It was a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation”. It was an irony of sorts from a man who called Gandhi a ‘half-naked fakir’.

On the other hand, the House of Lords took a different view that the House of Commons was unjust to the Officer. The Morning Post launched a patriotic drive for funds for the benefit of Dyer, portraying him as a victim. More than 26,000 pounds were raised. The butcher of Amritsar was given a full military funeral in 1927. Among the flowers was a wreath from Rudyard Kipling with the message “he did his duty as he saw it”!

Kipling was not alone in this adulation. Three days after the massacre Dyer was invited to the Golden Temple and offered a Sharopa. A shrine was also built at another Sikh holy place, Guru Sat Sultani. Most of the Anglo-Indian Community saw him as the ‘Savior of Punjab’. On the nationalist side, the Nobel Prize winner Rabindra Nath Tagore returned his knighthood in protest. Gandhi also returned the medals awarded for his wartime services. The massacre had the unintended consequence of catapulting Gandhi to unrivaled leadership of the Congress, side-lining moderates like C.R. Das, and Moti Lal Nehru.

David Cameroon, the British Prime Minister, visited Jallianwala Bagh in 2013 and wrote an apologetic message: “This was a deeply shameful event in the history of the British.” He was resonating the speech of Churchill in the House of Commons.

Amritsar’s tragedy of 1919 needs to be understood as the dying gasp of an imperialist ideology. The Rowlatt Act was quietly repealed. The British never used firepower on the civilian mob thereafter; even at the height of partition riots in 1947 in which Punjab witnessed the worst possible carnage. Wagner writes “We are not responsible for the past; we are responsible for how we choose to remember or forget the past. And perhaps there are wounds that we should not attempt to heal.”

Lt Governor Dyer who was absolved of his culpability by the Hunter Committee was assassinated in 1940 by Uddham Singh and his statue finds a pride of place in Jallianwala Bagh. The violent & valorous leitmotif of Bhagat Singh & Bhagat Singh was changed by Gandhi, who made non-violence his unshakable credo in life, as India inched towards independence. The scars of history cannot be erased. Possibly, the most poignant lines were written on Jallianwala Bagh by the poet Subhadra Kumari Chauhan:

Alas! This lovely garden is drenched in blood

Come spring, dear king of seasons, but come quietly

This is a mourning – place, so make no noise.

(The writer is a Professor Emeritus, KiiT University, Bhubaneswar. Views expressed are personal.)