Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali not only redefined Indian filmmaking but also earned global acclaim, making him a towering figure in world cinema

Satya Narayan Misra

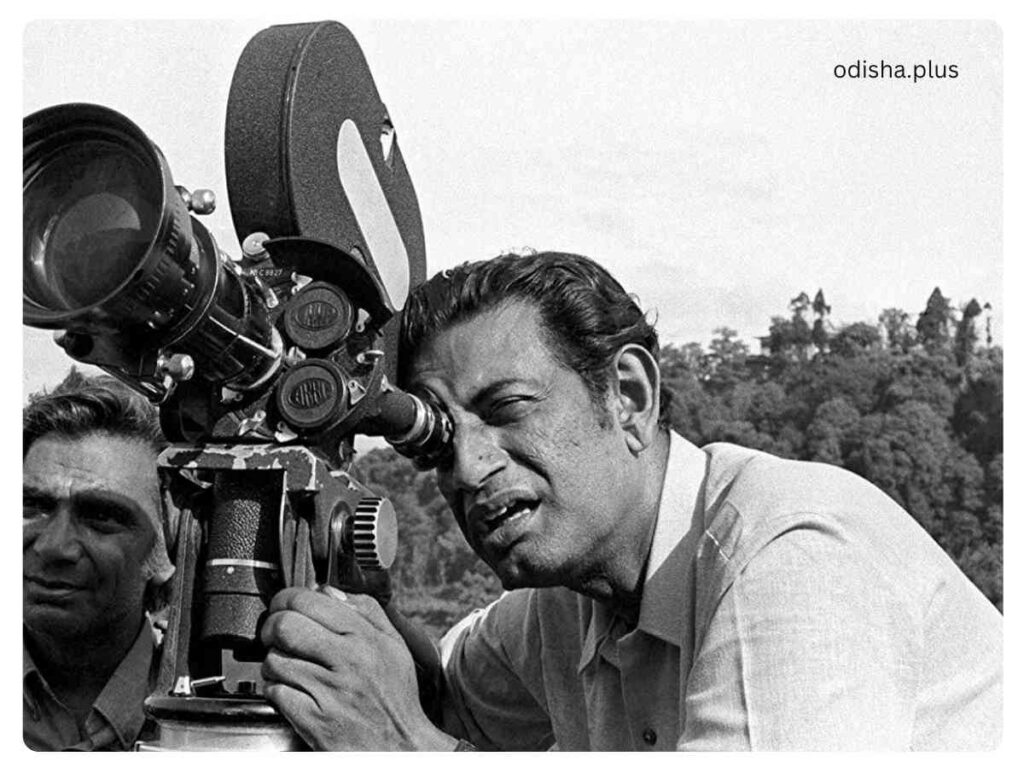

Satyajit Ray breathed his last on 23rd April, thirty-three years ago. By common consent, he is the tallest director who straddled Indian cinema, beginning with his iconic film Pather Panchali released in 1955, heralding a new wave both in Bengali & Indian cinema. Time magazine identified the hundred greatest movies during the last ten decades, and the lone Indian movie that finds a pride of place is Pather Panchali.

He helped Jean Renoir during the shooting of The River, and during this time, Ray shared his plan to adapt Pather Panchali, based on the novel by Bibhuti Bhusan Bandopadhyay. Despite financial struggles, it took Ray three years to complete the film—an achievement against all odds.

Remarkably, it was his directorial debut, and his team was equally inexperienced: the cameraman had never filmed before, the actors were untested, and the music was composed by a young Ravi Shankar, who would later become a Bharat Ratna.

The story follows a young boy, Apu, who lives with his family in a rural village. The film was followed by two sequels—Aparajito and Apur Sansar—forming a trilogy that earned accolades at Cannes, Venice, and London. Ray’s use of background music was significant, especially in nearly wordless sequences like the rain scene and Durga’s death, where Ravi Shankar used classical ragas Desh and Todi respectively.

Ray’s cinematographer Subrat Mitra started with a 16mm camera and captured hauntingly beautiful visuals: forest paths, river vistas, and monsoon clouds. A particularly powerful moment is when the mother tends to her sick daughter in a storm, followed by a sudden cut to birds in flight after Durga’s death—an example of cinematic brilliance.

Ray’s films resonate deeply with Indian realities, reflecting the divide between modern and traditional, rich and poor. He imposed a calm and thoughtful rhythm in his storytelling, akin to the styles of Bergman and Antonioni. Ray’s portrayal of women was always sensitive, much like Tagore.

Ray believed movies are powerful windows into other lives and emphasized empathy through cinema. He was influenced by Italian neo-realism, especially De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, and initiated the film society movement in India in 1947. Today’s youth, accustomed to OTT platforms, might overlook classics like Pather Panchali for being black-and-white or slow-paced.

With the advent of Ray’s cinema in the 1950s, Indian filmmaking transitioned from sentimental post-independence narratives to more realistic storytelling, inspiring directors like Benegal, Sathyu, Adoor, and Aravindan in the 1970s. Ray’s contribution is not just cinematic; it’s historical—a bridge between past and present.

The author recounts watching Pather Panchali at the 1977 International Film Festival in Delhi and meeting Ray in 1987 at Nandan, where Ray humbly claimed his contribution was ‘creating an awareness of good films in India.’ Adoor Gopalakrishnan aptly called Ray ‘the most singular symbol of what is best and most revered in Indian cinema.’ As Akira Kurosawa once said, “Not seeing a Ray movie is like not seeing the moon and the sun.” Pather Panchali, even 70 years later, remains a peerless human document of global cinematic brilliance.

(The writer is a Professor Emeritus, KiiT University, Bhubaneswar. Views expressed are personal.)