Cinema is the language of not just the filmmaker but of the entire collective taking it with its culture, literature, language and way of life to a wider audience

Isha Isita

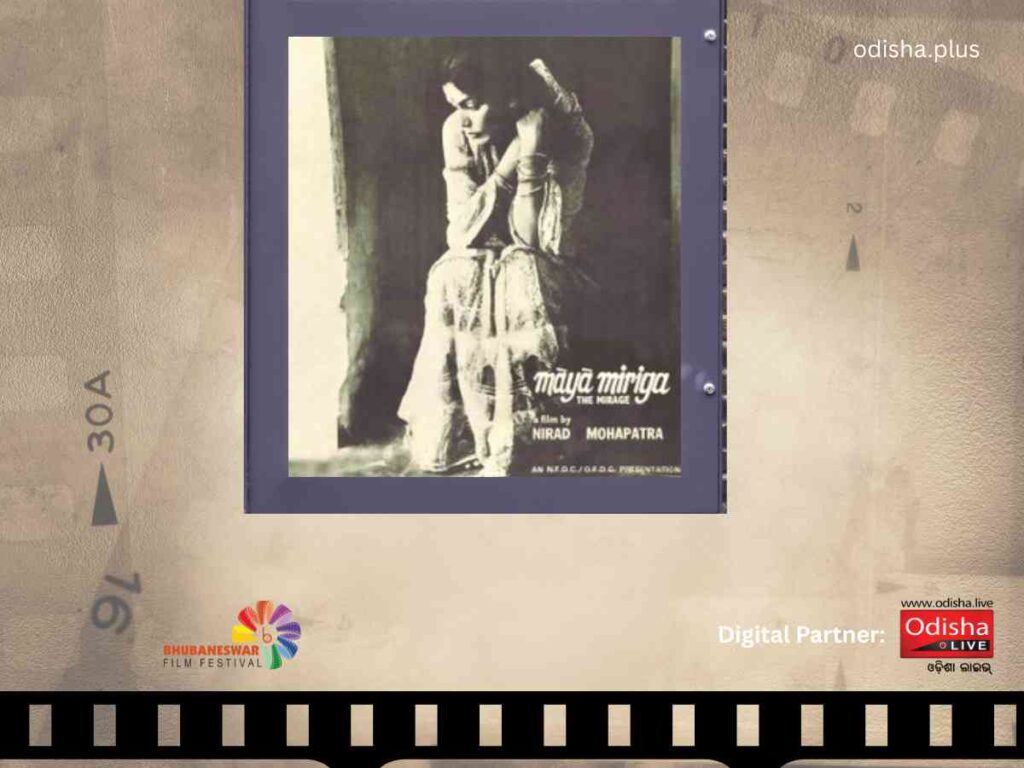

In a conversation with a very erudite film studies professor of my university about the politics and nature of regional cinema in India, I casually happened to mention Nirad Mohapatra’s lone masterpiece Maya Mriga (1984) as a regional work which had succeeded in capturing the uncertainty of dawning modernity after independence without undue melodrama, a feat hardly achieved by mainstream greats.

And (not) to my surprise he has never come across the film or for that matter any other Odia films classic or contemporary in research works published in the vast amount of film journals he had read.

The conversation soon turned into lamentation as we observed how less Odisha as a culture gets credible academic attention and research, despite being a minefield of intersecting traditions and rich cultural manifestations -literally a researcher’s dream. What exactly is the problem I wondered that night is it that we do not want to tell or the world does not want to listen, neither it seemed to me for I was eager then to narrate about my state and my professor was equally interested in Maya Mriga’s complex touch to the apparently simple subject of a family disintegrating.

Talking with friends and fellow researchers brought to my attention that their respective states had robust film ecosystems marked by frequently held and publicized film festivals, government funded research and creative works, and intellectual forums where the old classics were honoured and preserved, and a vigorous path was led open to the new darings.

Silently I had kept weeping for my state and its cultural industries which had seemingly been languishing in utter darkness until I came across the website of Bhubaneswar Film Festival organized in 2024 and their research compilation on Odia cinema Odia Cinema@90: Rhythms, Renditions and Reflections. Here at last was a beginning however nascent through which light can shine through on the past and present greatness of Odia cinema. And perhaps it can in due course become the guiding light for future consolidation of the struggling industry.

In 2024 the BFF which has been held from June 7th to June 9th had screened a host of meritorious Odia films which were a bouquet of diverse fames: it had old classics like Maya Mriga, it had standalones of parallel cinema like Shesha Drusti (1997), Shunya Swaroopa (1996) and Hello Arsi (2018), etc. and it even screened docu-films honoring past greats like Remembering Pramod Pati. Among them the honoured but forgotten classics of Odia cinema also found a new screen and a new audience, paving the way for their greater popularity and thus their greater homage. Films like Maya Mriga, Cha Mana Atha Guntha (1986) and Malajanha (1965) were screened and received with much enthusiasm, igniting hope that they will soon be accorded their rightful place in the study and history of regional classics of India.

In 1984 a brilliant film was quietly made by a director who quietly disappeared into the night after delivering a splendid performance to the muses of Cinema. Although it gained much critical and popular acclaim, the film was lost with the vagaries of time until Sandeep Mohapatro, the son of the maestro and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, the Director of Film Heritage Foundation took onto themselves the Herculean task of restoring it from its tattered negatives(that’s a story of perseverance which deserves an article on its own).

Nirad Mohapatra’s sole cinematic work, Maya Mriga as a film has become synonymous with Odia cinema and perhaps to my pathologically poetic mind with the Odia culture itself. Following in the footsteps of Ray and Ozu, yet remaining adamantly Odia in its individuality, this lyrical work sees a typical middle class family grappling with contrasting pulls of ambition’s inherent need for individuality and the silent sacrifice that the togetherness of emotional bonds demand, especially from the women of the family.

The film, its characters and its audience helplessly watch as the family unfolds, knowing what has to happen is going to happen and there is no way to change back the hands of the clock, no matter how painful the scene it stops at.

Similarly, Nitai Palit’s 1965 tragedy Malajanha adopted from Upendra Kishore Das’ novel of the same name follows a young Sati (the charming Jharana Das) through the tribulations and trials of female life in caste and gender segregated rural Odisha where feudalism was the law of the land. Unconventional for its glaring honesty, it’s the cinematic embodiment of the silent tears of Odia women as they went on satisfying patriarchal mores which held women and men to separate standards, prescribing the cloistered rigid veil of virtue to one while the other was left scot-free to succumb to moral degradation.

The film, which faced much financial trouble to see the light of day, has a compassionate and rageful gaze on womanhood and the fire trials demanded of it, which combined with a haunting music track composed by Akshaya Mohanty refuses to be seen without denting a hole in your psyche.

When Fakir Mohan penned his magnum opus, he gave the world one of the most intelligently structured subaltern novel to exist in Indian literature with its wretched characters, the cry of village distress in its fluid rural tongue and the despondent realism that no matter that runs the reign, the blood and tears of the innocents would flow.

Parbati Ghosh whose contribution to Odia cinema cannot be understated adapted the novel to the camera in a laudable attempt to cinematize the classics of Odia literature. Although the film, according to many critics, failed to capture the complexity of narrativization and equanimity of vision of the great novel, in defense of Ghosh the intensity of Senapati’s novel or rather his epic is impossible for any lesser mind to capture and convey. But the film can serve as a new generation’s first exposure to the novel which can be daunting at a first glance. That being said, Odia cinema has to come a long way before it can do justice to the rich tradition its literature has left for it.

The reason why festivals like BFF are so indispensable not just for the film ecosystem but also for the healthy nurturing of the culture in itself is because cinema and the motion medium has become the new creative communication channel for the new world. So when classics are screened at such festivals, and when critics and laymen alike discuss it and write about it, it paves the way for the culture to travel with its cinema to unheard corners.

Cinema thus becomes the language of not just the filmmaker but of the entire collective taking it with its culture, literature, language and way of life to a wider audience. I laud the nascent steps that Bhubaneswar Film Circle has taken towards this lofty goal by paying homage to lost Odia classics in its Festival and hopefully it will soon show the way for a deeper intellectual ecosystem to develop the languished industry of Odia cinema and Odia culture in overall.

(The author, a student of English Literature at Christ University, Bengaluru is an intern with Bhubaneswar Film Circle. Views are personal.)