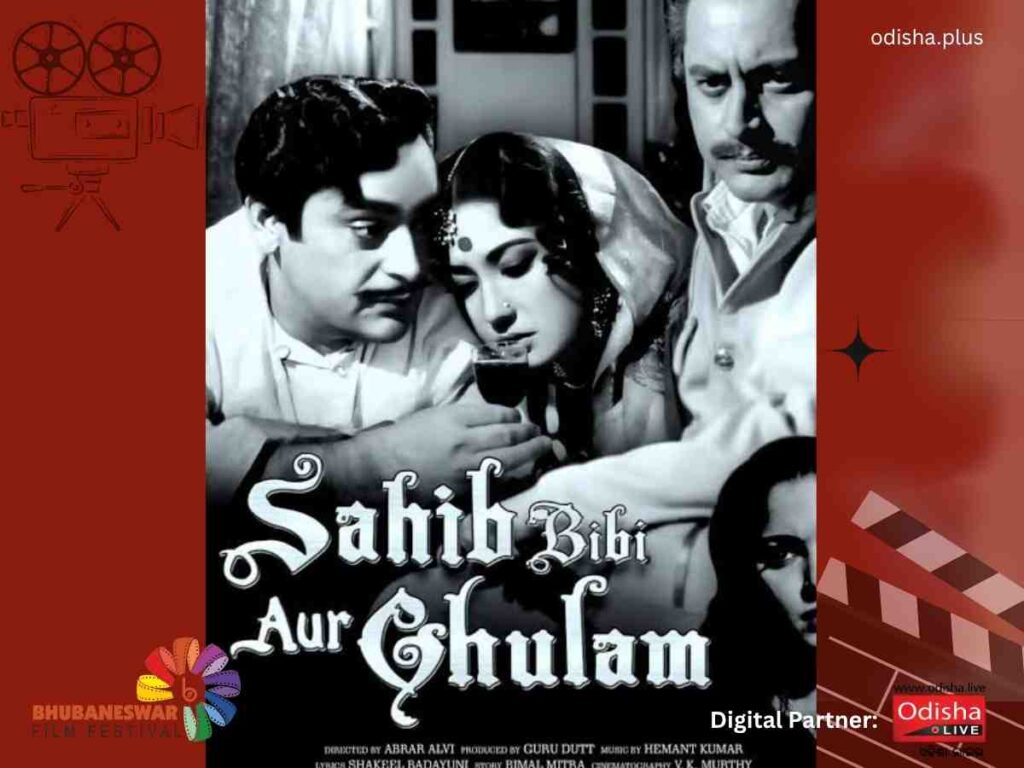

A cinematic gem, Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam captures the fading grandeur of Bengal’s feudal past and a woman’s silent rebellion

Isha Isita

A fascinated Bhootnath(Guru Dutt) steals a glance from the parting Jali(decorated window) of an opulent Haveli to watch star-struck the beauteous moves of the Haveli courtesan (Minoo Mumtaz) as she entertains the feudal landlords of Bengal. The dancer flirts in and out of darkness and dim light, while Bhootnath lies hidden in semi-darkness and the landlords are under the bright light which strangely appears black and ominous. In one single shot, without speaking a word the cinematography of V.K.Murthy has opened before us the dynamics of the British-era Bengal feudalism where the Zamindars ruled in short-lived arrogance, and the populace remained hidden servile in darkness, and the women clothed in the oblivion of Zenana and when out of it merged with the cloistered silence of exploitation.

Throughout the film let it be in Chhoti Bahu’s(Meen Kumari) elegant introduction where the light travels from her foot and settles on her Sindoor, leaving her in darkness or the scene where Jaba(Waheeda Raman) in darkness wonders who would be her childhood betrothed while Bhootnath stands in light indicating his knowledge of the information, the light and shadow speak more than the words do. And that is the beauty of Sahib,Bibi Aur Ghulam.

Burrowed from Bimal Mitra’s 1953 novel of the same name, the film is a melancholic chronicle of a decadent Zamindari system in Bengal which eventually fell prey to the same exploitative selfishness that they had unwittingly given rise to. But the feudalist Zamindari is not the protagonist emotion of the film, instead it is the pitiable pining of an isolated women which is the main cry of the film that follows Choti Bahu as she yearns for her squandering husband’s(Rehman) affection and loses herself to alcoholism in the process.

More than the wanton Zamindars the film focuses on their wasting wives who are psychologically and physically isolated from the world and destroy their lives cloistered in silent endurance of the exploitation meted out to them by a society seeping into rigid patriarchal feudal demarcations and bear all of their purposeless life without a murmur as pointed out by Choti Bahu’s husband as he objects to her persistence – “Gehnetudwo, gehnabanvao. Aur koriyankhelo.

Sho Aram se”(Break old jewelry sets, make new ones. Play with shells. And sleep). But unconventionally she persists and realizes her frustration when her husband does not respond to her advances even after she has spiraled to alcoholism for him. In the end her rebellious desire to seek affection and urgency ends in herin-law’s brutal murder of her, showing the fragility of women lives when society descends into orthodox decadency.

Although the film was a commercial failure as the conservative audience reacted negatively to the audacious portrayal of an alcoholic Thakurain as a central character(Rangoonwala*), history recognized the brilliancy of this poetry in motion and applauded its lyrical honesty in painting the faded world of the Bengal feudal lords replete with hidden sighs, opulent dissolution and the slow poison of inertia and exploitative arrogance gnawing away at its roots, preparing Bengal for a complete imperial domination.

Although burrowed from Mitra’s popular novel, Guru Dutt and Abrar Alvi lend their poetic aesthetic sensibilities to the story transforming it from a plain commentary of the times to a haunting wail of a sorrowing trapped woman whose falls symbolizes the fall of Zamindari system and the fall of Bengal as a force. Perhaps the most impactful role of Meena Kumari’s career, her mystery-filled portrayal of the pining wife became an iconic symbol of not just the movie but of Guru Dutt’s filmography as a whole. The shot of her pensively stretched out on her Divan clad in her fullest finery is as remarkable an example of Dutt‘s motional language as the parting shot of Kaagaz Ke Phool(1959) where the tired filmmaker lets his cigarette fall out of the window in a last performance.(*Rangoonwala, Firoze – Guru Dutt, 1925–1965: A Monograph. National Film Archive of India. OCLC 612789499, 1973.)

To the impeccable direction and the moving cinematography, Hemant Kumar’s haunting soundtracks give a befitting complement. Dutt craftily uses the soundtrack as the innerrepressed voice of his female characters who are restricted by their caste and gender positions to speak their mind aloud. The still expectant Choti Bahu expresses her inner desire for her husband’s love as she hums “Piya Aiso Jiya Mein Samaya Gao”(sung by Geeta Dutt) and is evocative in its honest exploration of a new bride’s eager excitement.

Her love crushed, her expectations smashed, with hemlock in her tongue instead of flowers the betrayed wife pleads her wanton husband in “Na Jao Saiyan Chhuda Ke Baiyan’’ (also sung by Geeta Dutt) and when her supplicant pleas fell on deaf ears she declares defiantly her persistence in yearning her rightful place in the marital bond : “Jo muzsseakhiyanchurarahe ho / To meri itniarajbhi sun lo /Tumharecharnonmein aagayihoo/Yahi jioongiyahimarungi” ( Because you are stealing glances from me listen to my last plea. I have come to your feet, now if live I will live here, if I die, I will die here).

Similarly, Jaba teases Bhootnath through her playful “Bhanwara Bada Nadan“and pens her frustration and regrets in “Meri Baat Rahi Mere Man Mein” (both sung by Asha Bhosle)which also is a veiled commentary on the repressed state of women in those times. Even the courtesans are given songs where they either assert their independence or wonder at their fragile position in the feudal ecosystem veiled as entertaining love songs.

Dutt’s Saheb, Bibi Aur Ghulam after decades of its release still remain a fascinating beautiful enigma with a haunting surreal play of light and poetry captured on celluloid. Its honest unconventional portrayal of a woman’s fatal search of love, its protagonist’s search for purpose and life, and its pathos-filled painting of a lost world makes it virtual poetry in motion, with each shot carrying a new revelation.

It’s a cinematic heritage that will remain forever an evocative tribute to the aesthetic mastery of Guru Dutt productions. It is a glad note that Bhubaneswar Film Festival is bringing this beautiful film to the doors of the Odia audience in its annual festival, paying fit respect to Guru Dutt’s legendary legacy. It is a matter of pleasure that film viewers should come to watch and appreciate one of the rare movies made by India where the light and darkness becomes narrators instead of mediums, and without words the pathos and ethos of a faded world is made alive and replete.

(The author, a student of English Literature at Christ University, Bengaluru is currently an intern with Bhubaneswar Film Circle. Views are personal.)