Bhaskar Parichha

The Exiled

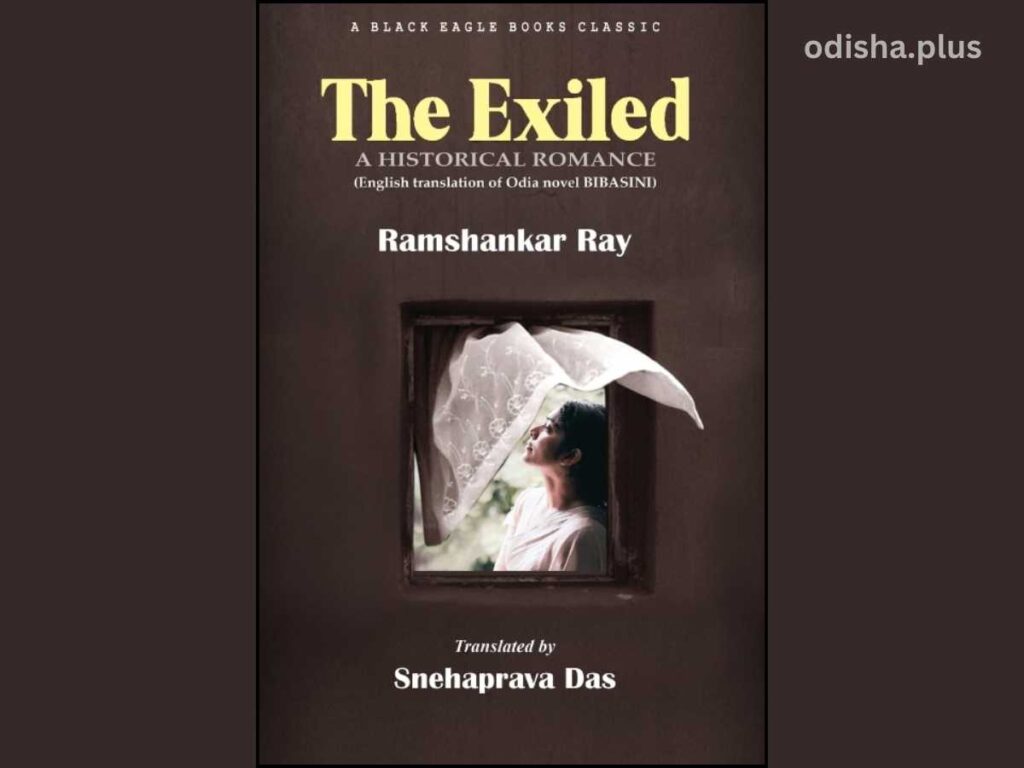

Ramshankar Ray /Snehaprava Das

Black Eagle Books

Bhubaneswar

Ramshankar Ray’s Bibasini, published in 1891, is considered to be the second full-length novel in Odia literature, after Umesh Chandra Sarkar’s Padmamali in 1888. The novel features a complex plot structure and is written in a style that is descriptive, informative, and lyrical. Often seen as a blend of historical romance and socio-political narrative, Bibasini is set during the Maratha rule over Odisha from 1751 to 1803. It provides a detailed account of Odisha’s struggles under the Maratha ruler Shambhuji Ganesh Rao from 1769 to 1771, as well as the resistance put up by the Bhuyan dacoits, supported by the king of Kujanga, Paradip, against the oppressors and collaborators. Bibasini by Ramshankar Ray has now been translated into English by Snehaprava Das.

Ramshankar Ray (1857-1931) was a skilled novelist and playwright. He released three novels (Soudamini, Bibasini, Unmadini) and fourteen plays (Kanchikaberi, Kalikala, Budhabara, Banabala, Badaloka, Bishwajajna, Bishamodaka, Jugadharma, Kanchanamali, Leelabati, Ramabanabasa, Kanshabadha, Chaitanyaleela, Ramabhisheka). In addition to his writing, he was actively involved in organizing theaters.

Ace translator Snehaprava Das, a former Associate Professor of English, is a distinguished poet and translator. She has translated many Odia novels, poems, plays, short stories, and non-fiction works into English. Dr. Das has authored five collections of English poems.

The present novel ‘Bibasini’ delves into a multifaceted narrative that goes beyond a simple tragic love story. It weaves together various random episodes to create a compelling tale of undeserved suffering, crime, vengeance, sin and retribution. The story is rich with characters from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds, each offering a unique perspective on Odisha’s social, cultural, economic and religious landscape. The novel vividly portrays the agrarian crisis in Odisha under Maratha rule, highlighting the devastating impact of famine on the peasantry. It sheds light on the hardships faced by common people, particularly farmers, who endured oppressive governance and the greed of wealthy local landowners.

The narrative further delves into the captivating tale of a band of robbers, motivated by an idealized belief in redistributing wealth from the affluent to aid the underprivileged, assuming the role of defenders of equality in society. They declare themselves as the moral guardians of divine retribution towards the undeserved. At the same time, the book conceals a commentary on the shallow principles of a societal framework that compels a Hindu widow to conform to religious austerity and denies her the chance to experience a conventional woman’s life.

Prof. Jatindra Kumar Nayak in the foreword states: ‘The world neglected by historians has been explored by creative writers in their novels and autobiographies. The abbot of the monastery in Padmamali (1888) is a Maratha soldier who chooses to stay in Odisha even after the Marathas cede the province to the British. The central action of Bibasini (1891) unfolds against the background of resistance against Maratha misrule. It keeps shifting between Paradeep, where Robin Hood figures rob the agents of Maratha rule to bring succor to the oppressed subjects, and Cuttack, the seat of Maratha power. In this unusual endeavour they have the support of the king of Paradeep and the blessings of two hermits. One can easily detect the influence of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Ananda Matha here but there the resemblance ends. Regeneration of Hinduism is no part of the agenda of the author of Bibasini’.

Writes Snehaprava on the downsides of translating the novel : ‘Translating Bibasini, was by no means, an easy task. Being an early prose work in Odia authored by a Bengali writer, the language and style both posed considerable impediments to the task of the English rendering of the novel. If at one stage the sentences are crisp and brittle they are long and lyrically evocative in the next. The poetic descriptions the novel abounds in offer quite a challenge to the translator’s competence and craftmanship. The scene of the boat approaching the land narrated in the chapter three of the novel has a unique beauty that is difficult to be captured in its exactitude in another language’.

‘The Exile’ is a well-timed translation that highlights the significance of the novel genre. The novel form became prominent in Odia literature, coinciding with the rise of individualistic fiction exploring existentialist themes, and innovative writing after the groundbreaking publication of ‘Padmamali’. This, in reality, paved the way for the thriving Odia literary heritage of the 20th century.

(The author is a senior journalist and columnist. Views expressed are personal.)