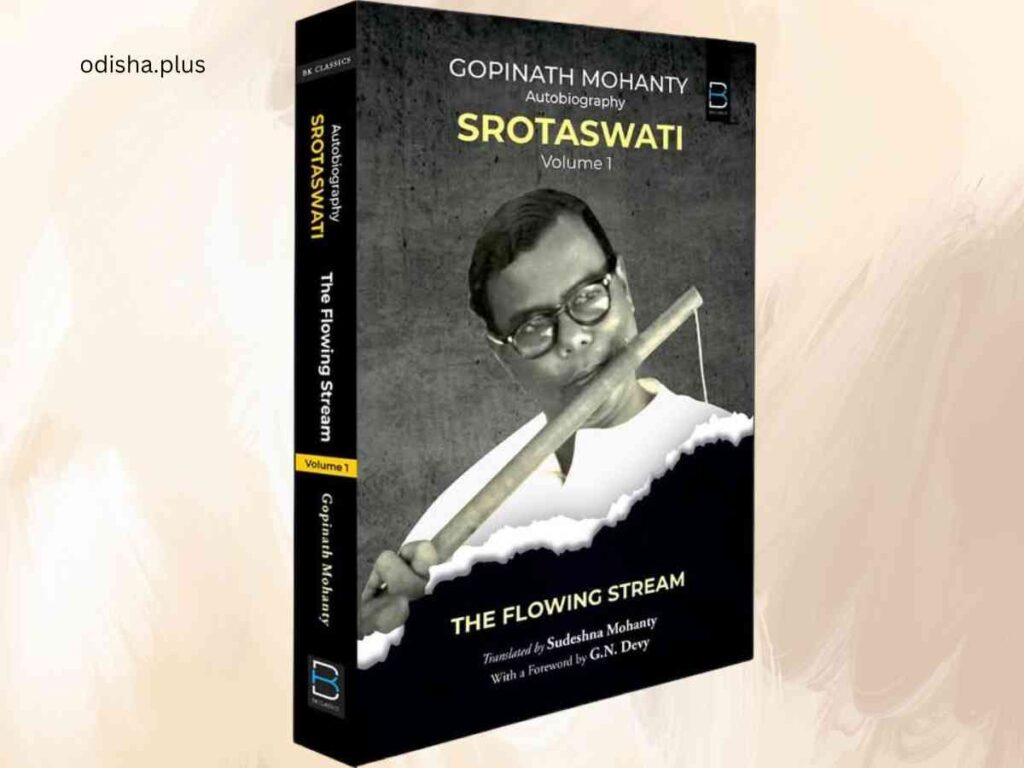

A lyrical journey into the past, Gopinath Mohanty’s ‘Srotaswati’ captures his birth, fading family legacy, and rural Odisha’s changing landscape

OdishaPlus Bureau

NAGABALI

That was a long time ago—fifty three years and four months to be exact—I started writing this autobiography on 23.08.1967 at 8:30 in the morning. That is where I was born; there—over there. Where both sides of the embankment have been eaten away by floods and the water gushes breathlessly as it flows towards the sea—I can only guess that that is where I was born; after so many years, I cannot exactly identify the place.

Stray notes scribbled in old diaries—raking them up takes me back thirty years. And then I stumble upon a notebook which takes me back another seven years, to 1930, when I looked at the world through the eyes of a teenager, a teenager looking at the world through the novel perspective that youth gives him. Some more rummaging throws up old, tattered school notebooks with a boy’s signature in English or O’Dea and Class VI or Class VII written on them. Some books are prizes won in school. I stumble upon them before they get lost again. But they do not date back fifty three years in time!

As I churn my memory, I go back further and still further far into the past—it’s amazing that I remember so much! The experience of the ear-pricking ceremony when I was four years, four months and four days old—there is no trace of that on my ears now! But before that?

The foundation for this presumption is an old birth chart drawn on palm leaf. With that, certain stories that I have heard.

Sometimes, I visualize the moment of my birth. A tiny, long, thin, red infant lying on a ragged mat bawling in the language of the other world, the world he has come from—who could say if that was a wail of distress or a cry of joy; a meaningful sound or a cry without any sense!

I remember Bou’s face. A full, round face. A face that resembled the face of the idol of Goddess Bhubaneswari of Bhubaneswar. The same rugged physique; I remember her lips, her nose, her eyes, her forehead, the stud on her nose and her nose-ring—her name too; it was Durga—Durgabati. Glimpses of my father’s face flash through memory—I was twelve when he passed away. His name was Suryamani. I remember too, many more faces; faces of people who jostled each other as they went about the house—a house the floor of which was mopped with a slurry of cowdung—a house that gave as much comfort as a mother’s lap; a thatched roof, the darkness that threw up moving shadows in the flickering light of the dibiri, the oil lamp—and then the raging fire and blinding smoke of the birthing room.

Mere guesswork, all this. Nineteen hundred and fourteen; 20 April. That was the date of my birth as per the English calendar, the Gregorian calendar. The time around 9.30 in the night. It was the month of Baishakh, an ekadashi, the eleventh day of the dark lunar fortnight I was born.

20. 4. 1914. According to the ephemeris, sunrise was at 05:12:03 hours and sunset was at 06:16:45 that day. The horoscope says it was a Monday, BaishakhKrushnaekadashi. The janmajakatanama, the birth horoscope name is GobindaSadhucharana, the shraddhanama, the nick name, Gopinath. The village, Nagabali. As you come from Cuttack, you walk across the bridge over the Kathajodiriver and then, turning left, you walk along the banks of the river. You walk for six miles, past Bharali, past Jharipada, past Khandayata and then arrive at Nagabali. The KathajodiRiver is called Sidua here, further down is the Debi River. After the great flood of 1935, when the river had breached the embankment in Khandayata, the geography of the area has changed. The embankment has become higher, Khandayata village has receded. Earlier, you could see the river from behind the family homestead. The homestead towered over the surrounding houses. It had many blocks of spacious rooms—now it lies bare; with sparse banana plants in our yard, and bare stretches of vacant land. My eldest brother, Giridhar, has moved north to a house beside the canal at the mouth of the village; his children live in their home in Dagarpara in Cuttack. The next brother, Jadunath, lives near Jagatsinghpur in Grameswar, Deuli. The third brother, Kanhucharan, lives in Rajabagicha in Cuttack. I live in Bhubaneswar. My dada, my father’s younger brother, Jagabandhu’s son, Artabandhu, has houses in Cuttack and near Mahidharapada. Guruprasad, the grandson of another dada, Dibyasingh, has a house in the family homestead true, but his family does not live there. My Badabapa, my father’s elder brother, Nilamani’s grandsons have built houses in Khallikote, Ganjam and live there. Very few members of the extended family live in the village now. A dada lives with his family—a son whom I call Narayana Bhai and his wife. A Badabapa’s grandson, Banabihari, is a widower; his son lives in Cuttack. Sometimes, Guruprasad’s mother comes to stay. That’s all.

This is an indication of how the winds of change have swept over an ancient, landed zamindar family and transformed it in fifty years! If you look down from the embankment, you can see a few shabby, thatched roofs scattered across the wilderness. A few ancient coconut trees, some crooked, some straight, some barren, some with a few fruits—they will not acquaint you with the story of bygone days.

This is the rear of the settlement. The front may, though, give you a hint of its glory. The northern side. A flight of steep steps that leads to a veranda. A row of rooms—its rafters and roof plates made of wood. Every inch of the wood is intricately carved. The thatched roof has rotted in patches, though.

The aristocracy of yesteryears! The small elaborately carved knobbed window frames have crumbled long since. Everything has changed. I feel like a refugee. While travelling by road from Bhubaneswar to Cuttack, I turn my face towards Nagabali and bow my head in obeisance.

Ah! Atitaraatikranta! The past that is lost forever! Then too, the past had receded—then, when I was born. Bapa had resigned from his job as an overseer in Sonepur in a huff and had returned to the village. Many landlords had lost their zamindaris even before I had been born. What remained was the Telengapentazamindari and a few others. A few scattered patches of land. All leased land. However, convention still held well in some places and a lucky one would have a cultivated field here or a tract there. These were let out for sharecropping. But the proceeds were meagre and barely enough to provide sustenance for six months; the rest of the year one lived on a shoestring budget, buying what was needed.

My eldest brother was twenty two years old when I was born. He was a clerk in Patna in the Bihar secretariat; he sent home an occasional money order. My sister had been married into a family in Mahidharpada, four miles away from our village. She was our only sister, younger than my eldest brother. Her son, Suresh, was one-and-a-half months old when I was born. Getting a daughter married when he himself was unemployed, meeting the expenditure of the socially expected gifts that had to be sent to the daughter’s house—had taken their toll on my father’s finances. A two-year-old boy who was my parents’ second son, called Gopala, another boy a year younger than Apa called Bansi, and two boys, one of them called Satyapira—I had lost four brothers. Jadunath followed—Bou swept the dhuli, the dust in her yard with her bare hands as she prayed and made vows for the life of this, her sixth son—his pet name was Dhula. He was ten years old when I was born. Next to him was KanhuCharana, he was almost eight then. He was born on Jammastami. Bapa’s guru sat in the front veranda in front of the dhuni, the sacred fire, in the house where my parents lived in Sonepur. He suddenly announced, “Arey, Kanha has been born! Go into the house and welcome him!” Yes, he had! They, surely, were the much—desired offspring! But I?

The ninth child of Samanta Sri SuryanarayanaMohanty from the womb of his wife, a son! Bapa was nudging fifty. His strong, athletic physique had wasted away—he was fast embracing a yogic life with spiritual awareness and yoga; he sat in a yogic trance for hours; Bou was forty four. She had already brought eight children into the world. A once prosperous family had now fallen on bad times. Nobody would have prayed to the gods for another child to add to their woes. But they loved me more than life itself; my bhaujas, my elder brothers’ wives, teased me as Bou’s much pampered last born—the baby of the family.

Hot gusts of wind from an arid river bed on a dry, barren ekadashi in the month of Baishakh, on a pitch dark lunar fortnight. Dacoits ran wild; they pelted stones at the village in the dark to frighten the villagers. The huge kochila, strychnine tree that occupied about one acre of land a hundred yards down the path towards the river, was their hideout. The village dogs—the Bhalua, Tipu, Kalia, and Budhia of fifty four years ago serenaded the night in a declaration of solidarity. And then the jackals from the cremation ground on the other side of the embankment joined in the chorus. From the east, the west, and the south, the dogs picked up the rhythm of the “Bow-wow” song. These barks and whelps were like the mingling of the incantation of the Vedas, the ringing of church bells and call of the azan.

20 April 1914 The time had come. I was born.

(Extracted from The Flowing Stream – Gopinath Mohanty’s Odia autobiography Srotaswati, translated by Sudeshna Mohanty with the consent of the publishers BK Classics/Bhubaneswar)