Ritwick Ghatak was deeply involved in theatre, writing, directing and acting in plays

Mrinal Chatterjee

Ritwik Ghatak, one of the most brilliant filmmakers of India was born on 4 November 1925 in Dhaka, capital of present day Bangladesh. He is known for his bold, socially conscious storytelling. His films, such as ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ and ‘Subarnarekha’, deeply explored themes of identity, partition, and displacement, often portraying the struggles of marginalized communities.

Ritwick Ghatak wrote fiction for periodicals when he was young and then plays. He was deeply involved in theatre, writing, directing and acting in plays. Then he moved to film making. An apprenticeship with Nimai Ghosh, who made the first film in India on partition – Chinnamul in which Ghatak acted and worked as Asst. Director helped.

Ghatak’s unique narrative style and use of symbolism, use of music and sound effects made him a pioneer of Indian parallel cinema, leaving a lasting impact on South Asian film though he made just eight films.

His first completed film Nagarik (1952) took quite some time for release. It was released in 1977 after his death in 1976. Ajantrik (1958) Ghatak’s first commercial film as a director based on a story by Subodh Ghosh revolves around a taxi driver, Bimal (played by Kali Banerjee) and his car, Jagaddal, a 1920 Chevrolet Jalopy. It shows the attachment the protagonist Bimal develops for his car.

His next film ‘Badi Theke Paliye’ (1959), based on a story by Sibram Chakraborty was a children’s film, considered to be first in this genre in India.

His next three films form the much talked about partition trilogy.

Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), the first of the Partition Trilogy is considered one of the greatest Indian films ever made. It was critically acclaimed and a commercial success. The second of the trilogy, Komal Gandhar (1961) features a theatrical troupe. It failed at the box office and drove Ghatak into alcoholism.

Subarnarekha, the final instalment of the Partition Trilogy was made in 1962; but it was released in 1965. It tells the story of three refugees in West Bengal. Though critically acclaimed, it did not do well at the box office.

Consecutive box-office failure of two of his films somehow impacted him deeply. He left for Pune, worked as Faculty at the Film Institute, and then as Vice Principal. He made several short and documentary films.

A decade after Subarnarekha he made Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, based on the acclaimed novel by Advaita Malla Barman. Shot in Ghatak’s childhood home of East Bengal shortly after the independence of Bangladesh, the film captures the songs, speech, rituals, and rhythms of a once self-sufficient community and culture swept away by natural catastrophes, modernisation, and mass migration, like it happened in 1971.

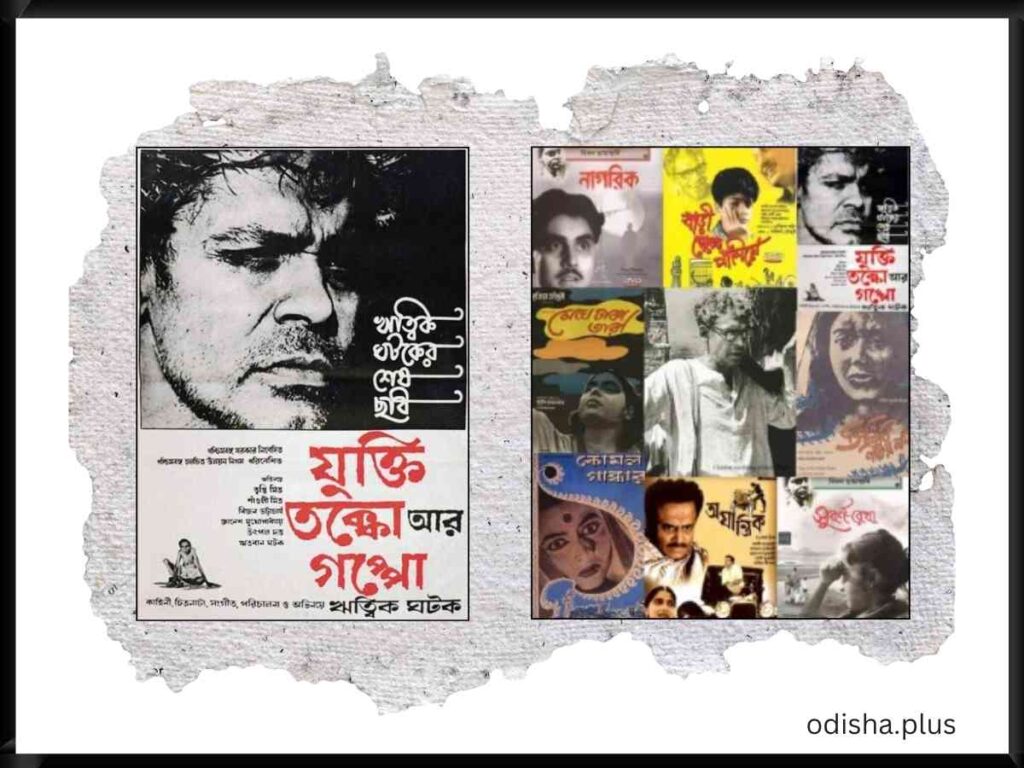

Jukti Takko Ar Gappo (Arguments and a Story) was his last film, which was released after his death. Loosely autobiographical, it was about a group of displaced, urban, lower middle class refugees.

Ritwick Ghatak was a maverick; and like most of the mavericks and geniuses had a tendency of self-destruction. He started drinking heavily after the commercial failure of Komalgandhar; and it continued.

He died on 6 Feb 1976 at the age of 51; he was suffering from tuberculosis.

50 years of Jukti Takko aar Gappo

‘Jukti Takko aar Gappo’ (Reason, Debate and a Story) was the last film of maverick filmmaker Ritwick Ghatak, which he wrote, directed and acted in. Loosely autobiographical, it was completed in 1974 but was released in 1977 after his death. It was not lapped by the audience, but gained critical acclaim worldwide.

The film merges philosophy, personal narrative, and social critique. Ghatak himself stars as the lead character, an alcoholic intellectual named Nilkantha, who embarks on a journey across rural Bengal. Through his encounters with a diverse set of people—a refugee woman, a revolutionary youth, and a disillusioned teacher—the film delves into India’s socio-political upheaval and cultural crisis in the aftermath of Partition and the Naxalite movement. It’s marked by poetic, often raw cinematography and Ghatak’s deep personal anguish, symbolizing the loss of cultural identity and values. The film critiques traditionalism and blind ideology, urging viewers to seek truth through rational debate. Ghatak’s semi-autobiographical portrayal highlights the conflict between individual ideals and societal constraints, making it one of the most intense cinematic reflections on human existence and Indian history.

It is available on YouTube. See the final film of a flawed genius.

‘?’ (Question Mark)

I was speaking on “Importance of Questions’ to a group of young lecturers and Asst. Professors this morning.

Ever wondered, why ‘?”- this symbol is used for the question mark.

As I gathered, it is unclear.

Some suggest it’s an ancient Egyptian symbol that emulates the formation of a cat’s tail when it’s inquisitive. The Egyptians loved and honored their cats.

Others suggest the mark emanates from the Latin word quaestio which means question. Over the centuries the word may have gotten shortened to a Q like symbol.

In any case, we, the modern readers, should be grateful for the invention of the question mark — otherwise we would have to do it ourselves.

Meanwhile my friend Prof. Umashankar Pandey says, the question mark is not there in Sanskrit. The presence of words like ‘kah’ (who), ‘kim’ (what), ‘kutah’ (where), etc. imply questions.

Golgappa

Gol Gappa (or Fuchka or Gupchup) originated in India, possibly from Raj-Kachori: an accidentally-made smaller puri giving birth to panipuri. It spread to the rest of India mainly due to the migration of people from one part of the country to another in the 20th century.

And now it has spread to the length and breadth of the country. I have seen people eating golgappa in Leh with the same pleasure as people in Kerala.

(The author is Regional Director Indian Institute of Mass Communication, IIMC Dhenkanal. Views expressed are personal.)